Part One: Bruichladdich Background & History

Nathan, The Scotch Noob

Jeff Schwartz, Whiskeyfellow

Introduction

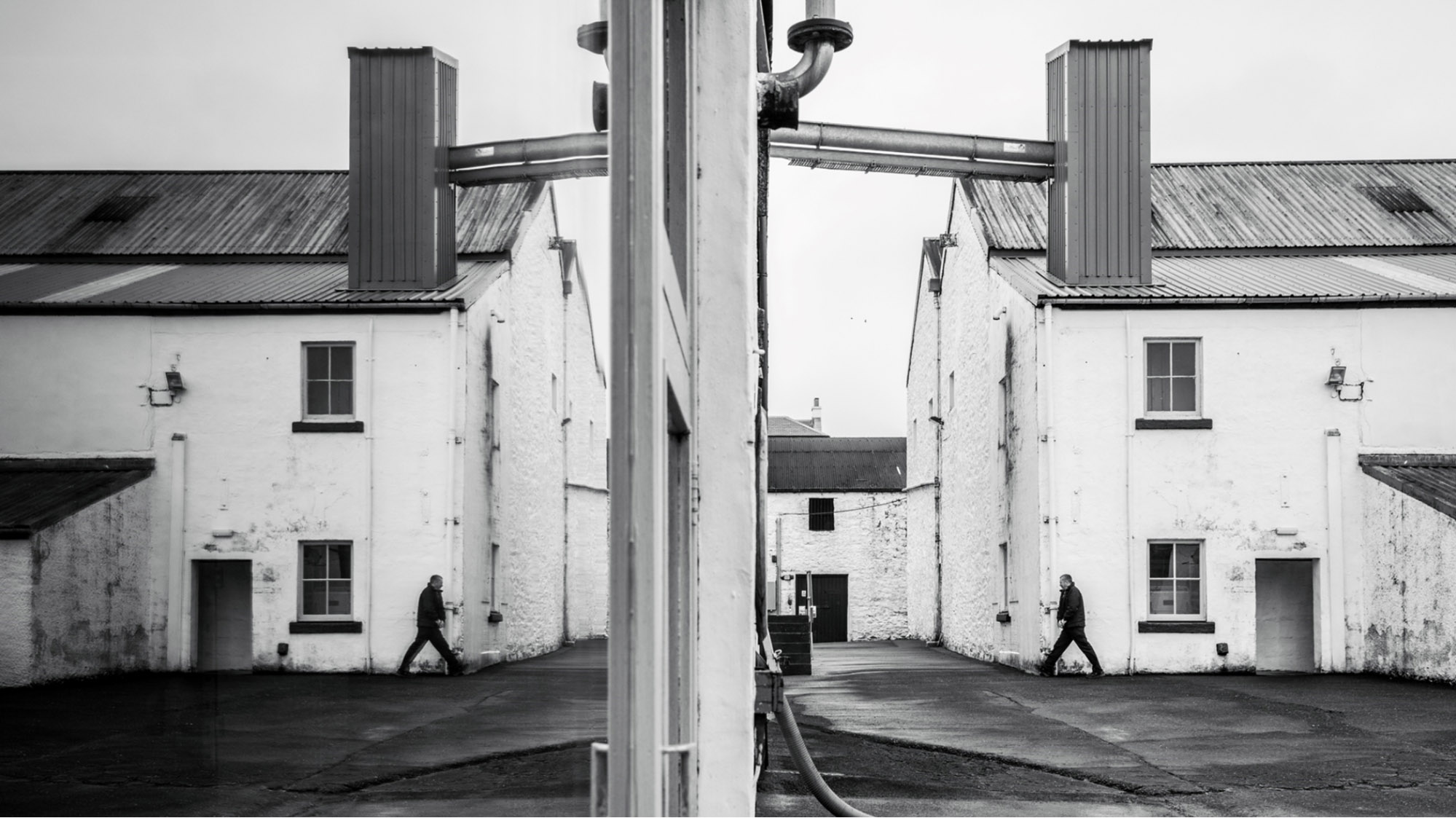

Bruichladdich is a place of contradictions. It’s a place shaped by the history of the people who lived and worked here, and it’s also a place where innovation and experimentation give birth to new ideas. It’s a place that has shifted from corporate ownership to scrappy independence and back, and it’s also a place that chooses to benefit its people and its community over the bottom line of a balance sheet. It’s a place where hand-operated equipment makes whisky that bears the fingerprints of the people who coax the Victorian mechanisms into life, and it’s also a place where the bucking of tradition is applauded if it results in a better spirit. It’s the contradictions – or the balance between them – that have molded Bruichladdich and its whisky.

A distillery isn’t just a collection of buildings and distilling equipment. It’s the sum of the people who have made their imprints on the community, on the machines, and on the traditions of craftsmanship that inspire and inform the people who operate it today. At Bruichladdich, they say that you can never manage to completely remove someone’s influence from a distillery, that you have to be respectful of who’s been here before and the stamp they’ve left on the place. That place, in turn, leaves its stamp on the whisky. It’s a whisky that can only have come from this place and could only have been made by this specific chain of craftspersons: From the farmer who grew the barley to the maltsters, still operators, coopers, and warehouse workers who turned it into Bruichladdich malt whisky.

Islay

Before we can understand Bruichladdich and its people, we have to first understand the individuality of the island of Islay. Pronounced “Eye-La”, the small island with a population not much above 3,000 people is the most southerly island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Its low-lying lands are fertile and well-watered by freshwater lochs and plentiful streams or burns, many of which flow through the island’s heather fields and peat bogs. While that may sound idyllic, the island is buffeted by strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean, and the weather is frequently inhospitable. The people of Islay – Ileachs – are few in number but fiercely proud of their rugged island home. As there are currently nine active distilleries on Islay, many of the people here are tied inescapably to the economic impact of the whisky industry.

Bruichladdich

Bruichladdich’s long story begins in 1881 when the Harvey brothers sealed a deal with a handshake and built the buildings and installed the stills that would provide the heart to their Glasgow-based blended scotch whisky. Bruichladdich’s tall, elegant, and narrow still necks would yield a lovely but light and floral spirit in contrast with the heavier style used by other Islay distilleries of the era.

The Harveys hailed from a family of distillers going back to 1770 and they meant business: They constructed what was (at the time) a state-of-the-art distillation facility, raising new-fangled concrete walls rather than the common approach of converting wood farmhouses. Alas, family strife hobbled the endeavor and the distillery was shuttered in 1907, leaving behind debt and large stocks of aging whisky.

The histories of many Scottish distilleries are peppered with boom and bust cycles, tragedy, closure, and frequent tumultuous changes of ownership. Bruichladdich is no different. After several periods of closure and with the business oft saddled by debt, the Harveys sold the distillery and its assets in 1937 to a Canadian entrepreneur and bootlegger named Joseph Hobbs, who added the facility to the portfolio of Associated Scotch Distillers. Despite a refurbishment in 1938 and the renewal of distilling operations after World War 2, Bruichladdich was sold no less than four times between 1950 and 1970, ending up in the hands of Invergordon (which later became Whyte & Mackay).

The 1960s and 1970s were good for Bruichladdich, which saw increased production at the cost of losing its “inefficient” on-site maltings, as well as replacement of its aging stills and the addition of a second pair of stills.

The good times ended, as they did for many scotch distilleries during the “whisky loch” era of the 1980s and 1990s. Sales were falling and distilleries were shuttered – many forever – all across Scotland. Bruichladdich lasted longer than many of its compatriots until Whyte & Mackay declared Bruichladdich “surplus to requirements” and shut down production in 1993. The distillery would sit empty except for 7,000 barrels of sleeping whisky for seven years while the rest of the whisky world enjoyed a renaissance and a new “boom” cycle.

Mark Raynier and Simon Coughlin

Mark is not from Islay, but he was often drawn to the magic of the place. He recalled cycling past the sleeping hulk of Bruichladdich behind its chained-shut gates and feeling called by the promise and legacy of the distillery. He was already a successful wine merchant when later in his career he founded the independent whisky bottling firm Murray McDavid. In 2000 he and co-investor Simon Coughlin marshaled funding and together with a cadre of shareholders purchased the derelict distillery. His first flash of genius was to hire Jim McEwan.

Jim McEwan

Jim is from Islay, born and raised. He had already spent a 38-year career working his way up from apprentice cooper to master distiller at Bowmore, just across the inlet of Loch Indaal from Bruichladdich when he got the call from Mark in 2000. Jim is an icon, a legend in the whisky industry. Anyone with ties to the business has stories about Jim, who could be entertaining a room full of Taiwanese whisky lovers one week and then formulating award-winning whiskies the next. Why leave a storied career to jumpstart a derelict distillery using no money? He says it was clear in a heartbeat.

Jim was tired from jet-setting around the world as an ambassador for Bowmore and the promise of resurrecting Bruichladdich while getting to spend more time at home on Islay made it an easy decision. Then he walked through the gates of Bruichladdich. “Jim,” he thought as he entered the bottling hall which was just four walls and no roof, “what have you done? This is a mess. You’ve just made the biggest mistake of your life, Jim McEwan.”

The Resurrection

Ileachs are not just stoic people, they are fiercely dedicated to their communities. Bruichladdich wasn’t just a factory down the road. Like many villages in Scotland, the towns of Bruichladdich and Port Charlotte had sprung up and grown around their respective distilleries. Bruichladdich distillery was the beating heart of the community there so it should come as little surprise that when the gates of Bruichladdich were opened the locals showed up with paint cans and wrenches and set to work, often without pay, restoring the place to some semblance of its former glory.

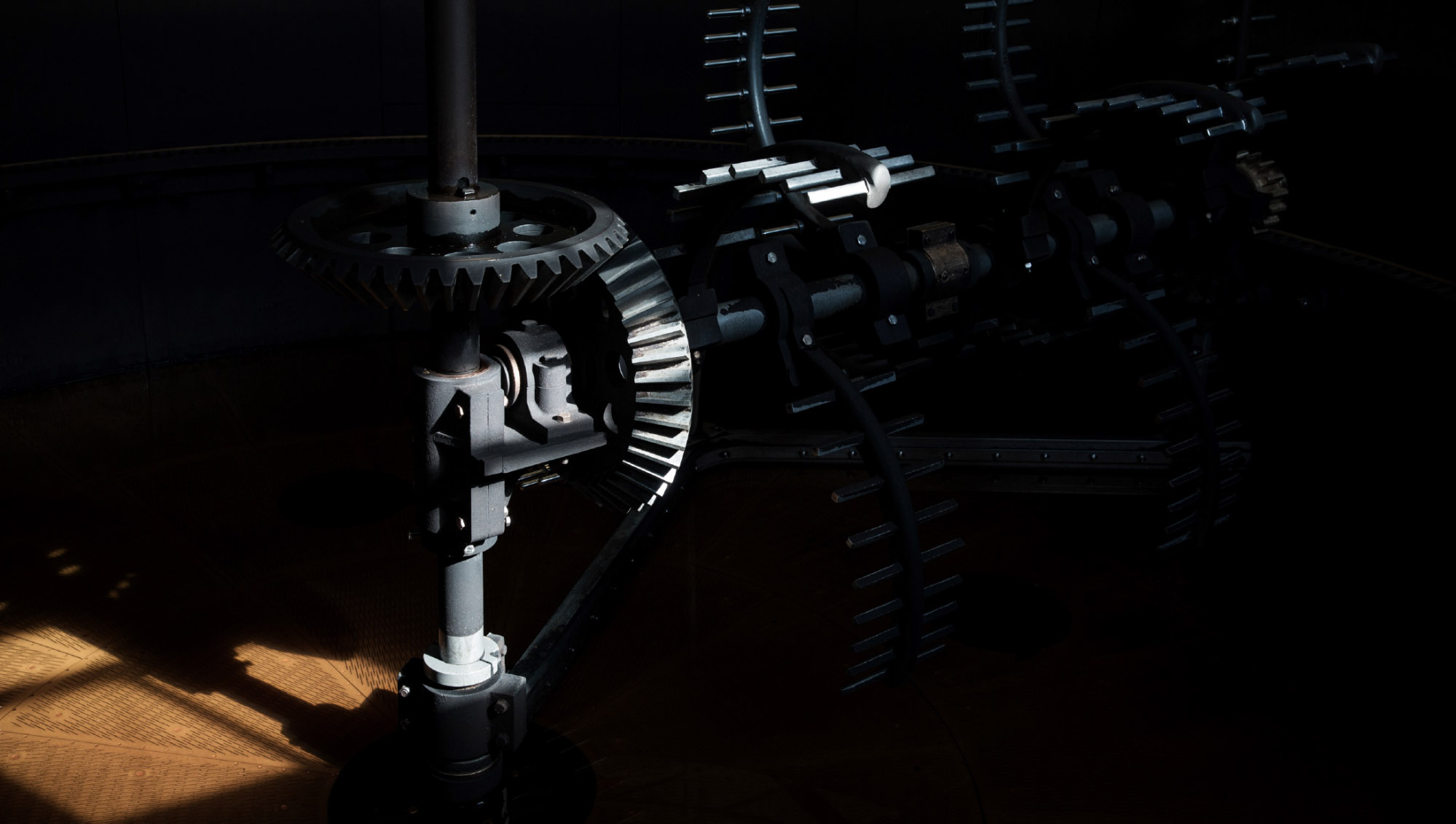

Most of the equipment had to be dismantled, cleaned, repaired and reassembled before any whisky could be made. Without much of a budget to work from, the team had to either repair broken equipment or find second-hand components to replace it. The still room had four stills (two wash and two spirit), six Douglas Fir washbacks that were 100 years old and have since been replaced, and a giant open-top cast-iron mash tun, one of only five left working in Scotland. From the grain elevators to the grist mill, most of the distillery was (and is) original to the facility built by the Harveys 120 years prior. It truly is a “working museum.”

Investors, critics, and others in the industry thought they were all crazy. “A money pit,” they said. “Without corporate sponsorship, it’ll never work.” The repairs were completed and by May 2001 the first spirit – from malt peated to 40 ppm and intended for the Port Charlotte brand – ran from the stills. Bruichladdich was back.

Being a young independent company came with pitfalls. Mark had to go back to investors three times with open hands for more funding. The aging distillery equipment required constant manual attention and repairs. To keep the business afloat, Jim worked madly to blend and re-finish the existing stock into limited-edition releases to sell. There were… a lot of releases, and although the whisky-appreciating public snapped them up and even developed something of a cult devotion to the upstart distillery, critics wondered if the many disjointed releases could ever come together into a stable portfolio. To make matters worse, within less than a year of the distillery’s reopening the Diageo-owned Port Ellen maltings renegotiated their contracts and forced Jim to look elsewhere for malt. He found it at small maltings in Inverness called Bairds.

Octomore

This turned out to be more than a happy accident. Bairds was willing to work in small batches (unlike Port Ellen) and was flexible with the payment schedule the struggling startup needed. Bairds was using an outdoor open peat fire, which meant the smoke levels were unpredictable and inconsistent. Because of this, the production process at Bairds involved blending extremely heavily-peated malt (80+ ppm) with unpeated malted barley to hit target peat specifications. Jim McEwan discovered this and with a proverbial twinkle in his eye, he asked what nobody else was asking: What if we distill the heavily peated stuff? The answer was unequivocal: “You can’t do that, it would be undrinkable.” You try telling Jim McEwan that he can’t do something. The idea for Octomore was born!

While in the midst of an ongoing quest to create the most heavily peated whisky in the world, Jim also managed to continue his focus on community and the local terroir of Islay. In 2006, local farmer James Brown (called by locals the “Godfather of Soil”) began supplying some of Octomore’s barley needs with Concerto barley from his Octomore farm. The farm is the definition of local and historic: first planted in the early 1800s by the Montgomery family, there was even once a shed with a small still to make whiskey from the farm’s barley using hand-cut peat.

Why use local barley? Farms in the fertile Scottish mainland are more efficient and can yield as much as 3.5 tons of barley per acre. The unforgiving Islay climate allows at most two tons, and not reliably. In the 2018 documentary film Scotch: A Golden Dream, Jim McEwan answered this question in his usual poetical style:

What makes this barley extremely special is the fact that it’s grown on Islay. And the soil on Islay is full of salt. Because next door we have the Atlantic ocean, so you can imagine the amount of salt that we get in our rain … How does that salty flavor manifest itself in the whisky? Barley grown on Islay has a fantastic fresh citrus lemon and honey flavor. The smell is just fantastic … just evocative of Islay.[1]

It was certainly not cost-effective to use the stuff: the lower yields and smaller batches meant higher prices, and the raw barley had to be shipped to Inverness to be malted to stratospheric peat levels by Bairds. As current Head Distiller Adam Hannett explains:

We’re committed to raising barley on Islay so that we can make Islay whisky with Islay barley because it feels good and tastes good to us. Financially, it’s suicide but when you taste it and you understand it and you feel it, that story, tasting that whisky when you know it’s come from one field, one farm, it makes that whisky alive. It’s not just the story, you can see the place, you can go there, you can stand in the field. It’s an amazing experience. That connection is what’s really important.

James Brown delivered the first harvest of Octomore barley to Bruichladdich himself, walking in front of the delivery truck in full kilt and regalia, playing the bagpipes to much applause.

Adam Hannett

Adam, another unassuming Ileach who eschewed higher education on the mainland to stay close to home and work at the distillery, began his career in 2004 as a tour guide and by tending the distillery shop. Just like Jim McEwan, Adam’s earnest work ethic gradually earned him opportunities to try his hand at every aspect of the operation, which gave him a thorough understanding of the entire distillery. He worked his way up to warehouse manager, where Jim saw his potential and recognized his latent talent and began grooming him to take up the reins.

Adam actually tried to leave once to pursue his career elsewhere but returned soon after, saying it was “the stupidest thing I’ve ever done.” Like others from the distillery, he knows that there’s “something about this distillery that when it gets under your skin… that’s it, no other distillery will do. The character of this place is incredible.”

In 2012, one year after Bruichladdich’s landmark first bottle of post-resurrection 10 year-old whisky hit the market,“fiercely independent Hebridean distiller” Bruichladdich was acquired by international conglomerate Rémy Cointreau, makers of Rémy Martin Cognac. Against Mark Reynier’s vote, the board of Bruichladdich accepted Rémy’s generous buyout offer. The industry at large, which had finally come to terms with the reality of Bruichladdich’s renaissance, reeled at the news.

Jim sees it differently. “Here was someone who got what we were doing, and saw value in it.” The buyout would remove money pressure, freeing the team and giving them confidence. The agreement also rewarded investors who had put endless faith in the distillery, including all of the staff, and Rémy promised not to interfere with what was working. This is a promise they kept: They didn’t change a thing. Mark Reynier, having seen his dream come to fruition but uninterested in going back to having a boss, passed leadership to his friend Simon Coughlin and left the company to pursue other projects.

The Internet – fans and critics of Bruichladdich alike – exhaled in unison when it became clear that Rémy Cointreau was not going to impede Bruichladdich’s independent and innovative spirit. Indeed, the new owners allowed Bruichladdich to keep putting its people and their community first.

In 2015, after winning the IWSC title of “Master Distiller of the Year”, Jim McEwan decided it was finally time to rest. He coordinated the handing off of his duties to Adam Hannett, who has assumed the title of “Head Distiller” instead of the more presumptuous “Master Distiller.

The Future

Bruichladdich’s redemption arc is a thing to behold. A veritable rags to riches story: from a derelict facility with four walls and no roof, the heart of a village that hadn’t beat in seven years, to an internationally-recognized engine of whisky innovation and the largest private employer on the island of Islay.

In May of 2020 Bruichladdich became a certified B-Corp, the first Scottish distillery to be recognized as such. The certification by B Lab marks Bruichladdich as “using business as a place for good.” To earn it, a company must meet environmental and social performance standards, operate transparently, and be fully accountable for its actions.

Still, Bruichladdich’s leadership feels they are “only halfway there,” with so many more positive moves to make for the distillery and its people. Plans are underway to add a maltings house, to bring some of the outsourced malting work home to the island. This is a money-losing proposition – it will always be most cost-effective to outsource maltings – but it brings another piece of the “100% Islay” puzzle together. It also brings jobs to the island.

So what does it mean to be a “Progressive” distillery of single malt scotch whisky, an industry steeped in tradition? It means innovating by exploring the infinite variability of raw natural ingredients such as cask types and barley varieties while remaining respectful of the recipes and distilling know-how of the past. It means being transparent, letting people know what’s in their glass while recognizing that what’s in the glass is also an indescribable chimera of all of the accumulated influence of all the people who came before. It means innovating by putting people – not profit – first, and yet remaining dedicated to producing the best possible spirit with, as Jim McEwan (who is already out of retirement, off to start a new distillery) puts it, “passion.” Because, he says, “if it’s not made with passion, it’s a mere shadow of what it could be.”[2]

The above is Sponsored Content in that I got paid to co-write it with Jeff, but all of the research and words are our own. For my own non-sponsored reviews, check out: Bruichladdich Octomore 11.1, Bruichladdich Octomore 11.3, and the 4th Edition of Octomore 10-year.

[…] Part One: Bruichladdich Background & History – The Scotch Noob […]

[…] Part 1: Bruichladdich Background and History […]

[…] Part 1: Bruichladdich Background and History […]